In June 1994, a wildfire swept through thousands of hectares in Chulilla and forced the evacuation of its residents. Today, three decades later, the landscape has largely regenerated, but the memory of the fire remains alive for all the people who remember that terrifying blaze and the mismanagement carried out by the Valencia regional government’s firefighting services.

The Black Summer of 1994

That year was one of the most tragic remembered in the Valencian Community: more than 130,000 hectares burned between June and September, with 13 fatalities in different incidents. In Spain, 1994 was recorded as a summer of “superfires” that tested all firefighting systems.

The fire that affected Chulilla was a rekindling of a fire that started in the area around the Loriguilla reservoir a few days earlier when sparks flew from workers of the Júcar Hydrographic Confederation who were doing ‘something’ in the area. The fire began in early June and soon spread through the pine forests and Mediterranean scrubland surrounding the Turia canyon. I remember that year perfectly. The drought was the worst I had seen up to that point and everything was very dry. Many springs had dried up. We had a heatwave with temperatures of over 40 degrees Celsius and dry thunderstorms.

The Fire

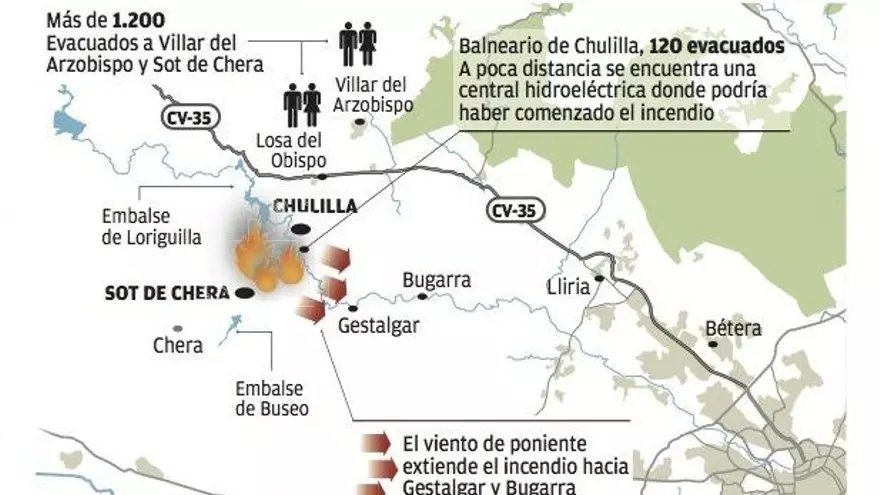

When the fire entered Chulilla, it did so from the west. The area opposite the Peñeta viewpoint is a shady area, and although it burned, the high humidity of the area slowed the fire down significantly, and many trees were unaffected. On one side, the fire moved east, towards the spa area, burning all the land that crosses the road from Chulilla to Sot de Chera. On the other side, and very slowly, it advanced northwards along the slope opposite the Trascastillo, that is, from the Cueva del Gollizno towards the Charco Azul.

This is where the conflict with the firefighting services began. Anyone with a bit of sense could make a prediction and deduce that the fire was heading north towards the Rambla de la Coneja, as it was estimated that it could cross the river’s narrow gorge and from there burn towards the Losa road and also approach the western slope of La Muela. In the 1990s, the open-cast mining work carried out in the area was still recent. Now, in 2025, the mine is almost completely covered by pine trees, and the ecopark is at the bottom. In 1994, that area was a wasteland with hardly any vegetation through which fire could not pass. Immediately, the people of Chulilla, including the mayor, realized there was a small ravine about 10 meters wide located south of the mine through which the fire could climb and burn La Muela. A counter-fire was considered—to burn the final meters of the ravine from the road, an area mostly surrounded by active, well-plowed crop fields. Currently, many crops have been lost in that area, but that was not the case back then. The process would be as follows: burn a few meters and extinguish it. Burn a little more and extinguish it again until a good area was cleared of vegetation. Counter-fires are used quite a bit today. It’s very common to see on television how wildland firefighters in Spain use this method on the sides of roads so that when the fire advances towards that part, it encounters the already burned area and stops. I have also seen its use in the major California wildfires. But in 1994, neither the bigwigs in charge nor the wildland firefighters in the area allowed the counter-fire to be set. Both on television and radio, they labeled the residents of Chulilla as hicks who didn’t know how to do anything, let alone put out a fire, even though the use of counter-fires was a traditional practice in Spain. The fire took hours to reach the area of the old mine, and under threats of legal action against the residents, the counter-fire was not set. When the fire went up that ravine, it crossed the road without any difficulty and burned La Muela.

The incompetence of the firefighting services generated great indignation among the residents of Chulilla. An extraordinary plenary session was convened to denounce the events, but I believe that beyond that, there wasn’t much more to the story. The government at the time promised more aid to the city council.

Errors in Firefighting

- Not allowing the use of counter-fires

- Insufficient aerial resources were used. As I mentioned before, the spread towards La Muela occurred from a very small ravine. A water bomber dropping retardant in the ravine area near the road could have changed the course of events, or even when the fire was advancing slowly in other areas. On this point, the excuse was the large number of fires occurring during those days.

- Oxygen bombs: I vaguely remember hearing about this. These would be bombs that, upon exploding, would deprive the area of oxygen and could extinguish the fire. They were discontinued due to their inefficacy. I have not found any official or unofficial media that mentions them in the Chulilla fire, aside from that article in the newspaper El País. It is true that there was a feeling of having been part of some government experiment. That was the result of so much incompetence.

- Poor management. As always happens during a catastrophe (see the 2025 wildfires in Spain), the chain of command becomes diluted and they either seem not to act or they make random or nonsensical decisions. Perhaps there are too few people with decision-making capacity in charge. Not everyone has the same knowledge (as demonstrated during the DANA [Isolated Upper-Level Depression] in October 2024). It was a true chaos. As an example, I always remember a helicopter pilot I knew who confessed to us that one of the orders he received was to dump water on an almond field far from the fire and return to base, even though he was en route to a fire front in Chulilla.

- Communication from the Valencia regional government: At that time, the person in charge was Vicent Baeza, who had been appointed to the position of Director General of the Interior in 1993, a hand-picked appointment by the PSOE. I remember his statements, which further inflamed the residents of Chulilla. A curious fact about this individual is that after demonstrating his incompetence in all these 1994 fires, and following a change of government in the spring of 1995 from the PSOE to the PP, he once again received a hand-picked political appointment, this time from the Partido Popular, as Head of Firefighters for the province of Alicante. I have always thought poorly of this man. Everyone can form their own opinion…

The Evacuation

On the morning of June 4th, the wind pushed the flames towards the town. Smoke filled the streets and the fire was visible from the town square. The authorities ordered the evacuation of about 700 people, who spent several hours away from their homes. The Fuencaliente spa was also evacuated.

The town was left without power or telephone service for part of the day, while forest brigades, helicopters, and water bombers tried to stop the advance.

The Damage Assessment

Official figures from the time estimated “more than 2,000 hectares” burned within the municipal boundaries. The regional government denied rumors putting the figure at 6,000 ha (the municipal area of Chulilla is about 6,400 hectares), and spoke of “no more than 2,500 ha”. Subsequent technical documents place the affected area at around 2,800 ha, including adjacent areas of other municipalities.

The most affected areas were the Pinus halepensis pine forests and Mediterranean scrubland, resulting in loss of biodiversity and severe erosion on slopes.

Wounds and Scars in Chulilla

For years, the hills to the west and especially to the north of the town showed a gray landscape, dotted with burned trunks. Gradually, nature reclaimed the land: today, young stands of Aleppo pine grow, with excessive densities in some areas that hinder biodiversity and increase the risk of fire.

The 2020 Technical Forest Management Plan warns that, although vegetation has returned, the forest structure is not the same and requires thinning and prevention work.

What Has Changed Since Then in Chulilla

The 1994 fire spurred improvements in coordination and resources at the regional level: more helitransported units, more robust communication systems, and local self-protection plans. However, climate change, the accumulation of fuel in regenerated areas, lack of forest management, and lack of active firebreaks (passive ones are useless) present new challenges that have yet to be addressed.

Chulilla’s Fire in 2012

The fire started around 4:28 PM on Sunday, September 23, 2012, right underneath an electrical tower located about 20 meters from the road and about 4 to 6 meters above it, on a slope of the Tabairas ravine. The investigation did not clarify the origin, but with the fire located directly under the high-voltage tower, a spark would be the most plausible option. I have seen similar fires where municipalities have sued the power company. In this case, no one did anything, and once again, there was no one held responsible.

As I recall, around 5:10 PM, my prediction was that the fire would burn in a northeast direction towards the Tabairas ravine, and once there, since the prevailing wind was from the west with gusts of 80 km/h, it would flow eastward and burn all the forest mass in its path. Reality exceeded this expectation, as it also spread through crop fields, even reaching Gestalgar, Sot de Chera, Pedralba, Bugarra, Casinos, and Domeño. And at a slower speed, it also burned the rest of its perimeter. The total affected area was about 5,500 hectares.

Errors in the 2012 Chulilla Firefighting Efforts

In this case, it is more complicated to find faults in the firefighting services, but there are debatable points.

Excessive time for someone knowledgeable to take command: A heroic account circulated on social media about a forest brigade that positioned itself in the Pelma area trying to do something when the fire was heading there with wind gusts of 80 km per hour. I consider it impossible that someone in command, seeing the wind speed and the topography, would send them to that position. It must have been a personal decision by the brigade, who acted more with their hearts than their heads. Fortunately, their recklessness did not cost them their lives, but it did waste precious time in containing the fire.

Specifically, there were two points where the fire passed and where more action should have been taken.

- To the southeast of the starting point: The fire spread very strongly up the Tabairas ravine and more slowly to the south, but when it exited the ravine, it continued with the prevailing westerly wind. This area does not have much forest mass, and the river is there. I do not have exact data on the work in this area, but the perception is that action was taken too late. The fire crossed the river, affected the spa, and began its journey south and east with almost no opposition due to the strong wind. A counter-fire early in the fire could have closed this perimeter, which by 5:00 PM was already seen as the immediate danger.

- To the west, La Muela: Although the fire was advancing very slowly to the west due to the opposing wind, it was one of the flanks where firefighting resources should have paid attention. The fire took a long time to cross the road and affect the La Muela mountain. The point where it passed to La Muela was small. So once again, this mountain burned.

How to Protect Against Fires in Chulilla?

The forest territory of Chulilla is determined by its rugged topography and the rivers that run through it. Both major fires started with westerly winds, which is typical. There was another fire in the 1960s that burned the area of La Bandera mountain and the river cliffs. This underscores that fires are not just a recent phenomenon or solely due to climate change, although its effects do accentuate them.

Contextual Elements and Solutions:

Land use has changed. 100 years ago, there were more heads of livestock than people, and all that livestock grazed the area. More people were in the town cultivating the land. Very few fields were inactive, and the forest mass was smaller. Much of the current forest mass is on mountain slopes with terraces. There was likely vineyard cultivation, and phylloxera caused the abandonment of those crops. On all those terraces, species that are not pyrophilic, like pines, should be planted.

| Type | Species (Scientific) | Common Name | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tree | Quercus ilex subsp. rotundifolia | Holm Oak | Very drought-resistant; low flammability. |

| Tree | Quercus faginea | Portuguese Oak | Prefers shady areas and more moisture. |

| Tree | Acer opalus subsp. granatense | Granada Maple | Cool areas of mid-mountain regions. |

| Tree | Sorbus domestica | Service Tree | Low flammability; promotes biodiversity. |

| Tree | Arbutus unedo | Strawberry Tree | Good ecological value; low pyrophytic nature. |

| Shrub | Quercus coccifera | Kermes Oak | Native and resistant, but pyrophytic (high flammability); recommended only in mixture and with management. The good thing is that it resprouts quickly and helps prevent soil loss on steep slopes. |

| Shrub | Rhamnus alaternus | Italian Buckthorn | Resistant; good understory. |

| Shrub | Phillyrea latifolia | Mock Privet | Very drought-tolerant; low flammability. |

| Shrub | Viburnum tinus | Laurustinus | Excellent in shady areas and ravines. |

| Shrub | Pistacia lentiscus | Mastic Tree | Lower combustibility compared to other rockroses/rosemaries. |

| Shrub | Crataegus monogyna | Hawthorn | Ideal for hedges; attracts wildlife. |

| Herbaceous / Ground Cover | Brachypodium retusum | False Brome | Stabilizes soil; low fuel load. |

| Herbaceous / Ground Cover | Helictotrichon filifolium | Rough Oat-grass | Alternative to more flammable esparto grasses. |

Avoid these species: Pines, Eucalyptus, Brooms, Rockroses, Heaths, Rosemary and Thyme in excess.

The topographic features of the area should be utilized as natural firebreaks. The abandoned fields in the river’s huerta (agricultural area) are a clear example of poor management. Partial actions are being taken against the reeds, which could improve this situation.

La Muela has been affected by these two major fires. Its connections to the rest of the forest mass should be protected and, to a certain extent, isolated. For example, after the 2012 fire, there is a large forest mass on the Losa road near the bridge. Thinning in this area would be fundamental if there were a fire prevention plan for Chulilla.

We have seen how firebreaks under power lines are of little use against a major fire. Nevertheless, to protect La Muela, an effective firebreak should be created, and I can think of two options:

Wet and Green Firebreaks with Irrigation (also called productive firebreaks or irrigated green firebreaks) are an increasingly considered strategy in Mediterranean areas.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

Firebreaks with Cypress Trees

This type of firebreak was initially based on an experimental plantation in Jérica that the 2012 Andilla fire could not destroy. There were many international scientific studies stating that a specific species of cypress (not the common cemetery or hedge type) was somewhat more resistant to burning than other species.

There were also opposing opinions, claiming they didn’t burn solely due to the action of a path that acted as a firebreak. These opposing opinions have never addressed the other studies indicating that the Cupressus horizontalis was more resistant to burning than other species, nor the recommendations for their use in firebreaks.

After reading all the information, it seems clear that a path or grazed area alongside three rows of cypress trees could work quite well. However, it is currently unfeasible as saplings of that type are not available in Spain. They were given away because the project depended on an organization accused of corruption. Therefore, the idea of surrounding La Muela with a path for hikers flanked by cypress trees is unaffordable. Nevertheless, in areas with the highest probability of fire spread, it would be advisable to alternate areas of different vegetation alongside that hiking path. Another more tourist-friendly route could be created, also signposted along the eastern face of La Muela.

Key Points About Imelsa and the Use of Cypress Trees as Firebreaks

-

Andilla Fire (2012): An experimental plot with 946 cypress trees was surrounded by fire; the experimental cypresses showed high survival (~90%).Sources: Europa Press, Público (summary).

-

Pilot Scaling (2014–2015): Imelsa promoted the planting of ~10,000 selected cypress trees in various regions of Valencia to evaluate their preventive and productive use.Sources: Pre-portal Dival, Levante-EMV.

-

Dissemination and International Recognition: The project was presented at MED/EU forums and the horizontal variety of cypress was incorporated into regional regulations (e.g., Tuscany) as a species of interest for firebreak strips.Sources: El Periodic, La Vanguardia.

-

Scientific Results and Analysis: Studies and technical notes indicated low ignition percentages in the experimental plots (e.g., ~1.27% in some analyses) and physical conditions (moisture, canopy architecture) that explain the observed resistance.Sources and reports: Levante-EMV (study summary), SDL Medio Ambiente (analysis).

- Criticisms, Limitations, and Rethinking: Technicians and firefighters warned that survival may have been due to context (clean plots, cultivated behavior) and that cypresses are not a universal solution; public management (Imelsa → Divalterra) reviewed/slowed the project due to technical and environmental doubts.

More sources:

https://www.greenreport.it/news/natura-e-biodiversita/15902-lenigma-dei-cipressi-che-resistono-agli-incendi-uno-studio-italo-spagnolo

https://metode.es/revistas-metode/llibres-revistes-revistes/el-sistema-cipres-de-barreras-cortafuegos-y-monumental-trees-and-mature-forests-threatened-in-the-mediterranean-landscapes.html

https://www.lavanguardia.com/local/valencia/20141123/54419631392/la-toscana-incluye-el-cipres-como-especie-preferente-para-los-cortafuegos.html

https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/08/150827_cipres_incendios_enigma_am

https://www.eldiario.es/sociedad/investigacion-cipreses-cortafuegos-acabara-plantas_1_3814570.html

https://www.elmundo.es/comunidad-valenciana/2016/10/12/57fd309fca474134418b45d0.htmlhttps://silvicultor.blogspot.com/2012/08/cipreses-ignifugos-algunos-comentarios.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20230614024934/http://cupressus.ipp.cnr.it/cypfire/cypfire_prodotti2.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20160222034836/http://cupressus.ipp.cnr.it/cypfire/files/Sistema_Cipres_cap6.pdf

https://www.elmundo.es/ciencia/2016/10/11/57fbeddb468aeb750d8b4608.html

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301479715300724

Slides Cypfire project 2009 – 2012

Cypress and forest fires: a practical manual

Implementation of the « cypresssystem » as a green firewall

This is quite the scorcher of an article! Its fascinating to dive into these past fires and the comical chain of errors – ordering helicopters to water an almond field while the inferno rages nearby is peak absurdity. The recurring theme of the incompetent decision-makers and the baffling persistence of certain strategies (like those oxygen bombs!) makes for a wild read. Its almost comforting to know that despite the advances mentioned, the potential for utter chaos remains, especially with climate change throwing a wrench in the works. Honestly, if these firebreak ideas worked perfectly, we probably wouldnt have such engaging stories, right?

The history tell us how fire and humans destroy the nature. what a pity!